On July 27, 2019 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) published a proposed rule regarding the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (“PFS”) and other Medicare Part B (“Part B”) policies. The proposed rule outlines numerous changes; however, one of the most controversial may be the the approaches related to work RVUs.

According to CMS, the work component of the RVU is meant to cover the portion of the resources used in furnishing physician services. In short, it attempts to value the provider’s (MD, DO, NP, PA) time and the intensity of the services. This system was developed through a partnership between the Department of Health and Human Services and Harvard University. This methodology for capturing time and intensity of services has been in effect since January 1, 1992.

With respect to the proposed rule, certain Evaluation & Management Services (“E&M”) are covered under CPT codes that have three components: History of Present Illness, Physical Exam, and Medical Decision Making. In addition, there are three to four levels in the inpatient and nursing facility setting, and five levels in the outpatient setting. The levels are meant to cover the level of complexity of the service.

Proposed Changes to Office Visit Payment and Work RVU Rates

The proposed changes would only apply to office/outpatient visit codes (CPT 99201 – 99215). CMS is proposing multiple reductions in documentation requirements; however, the biggest change comes in two different forms. First, CMS is proposing that there be a single payment rate for Level 2 to 5 office visits. Second, CMS is proposing that there be a flat work RVU amount for Level 2 to 5 office visits.

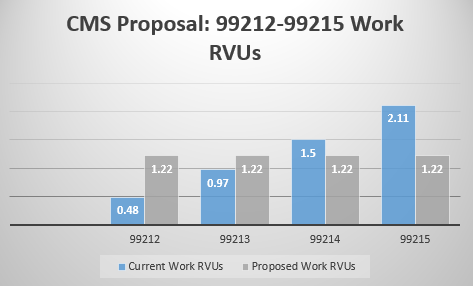

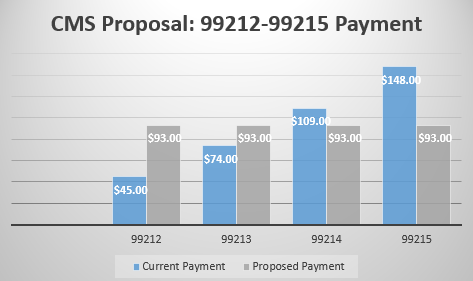

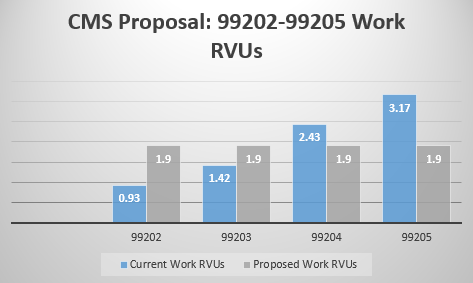

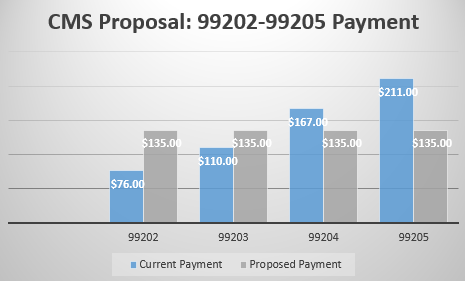

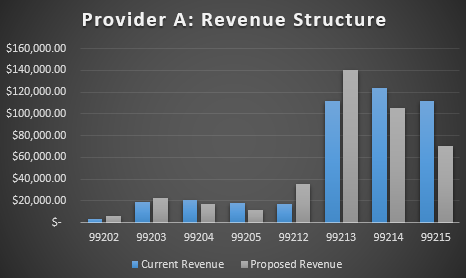

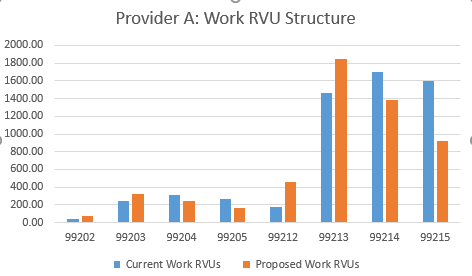

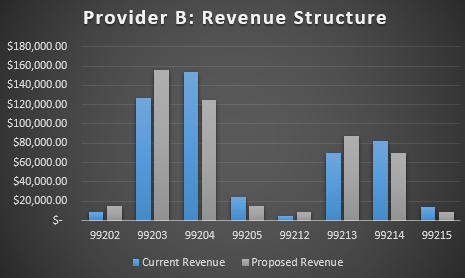

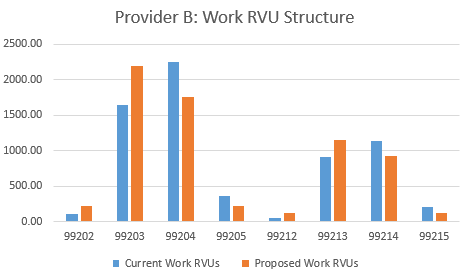

The payment rate for 99212 – 99215 will be $93 per visit and $135 for 99202 to 99205. With respect to work RVUs, CMS is proposing 1.90 work RVUs for 99202 – 99205 and 1.22 work RVUs for 9912 – 99215. CMS states that these inputs are based on an average of the inputs for the individual codes, weighted by volume based on utilization data from the past 5 years. Below is a visual of these changes:

As you can see from the above charts, whether an individual or entity benefits from this change depends on a few different assumptions. First, from a financial end it is possible that an individual who is regularly billing level 3 visits creates a windfall for an organization. For example, if an organization has a well-developed urgent care clinic model, it is highly probably that business unit would benefit due to this change. However, using a few examples we can visualize the possible scenarios.

Provider A

Provider A is an establish family medicine provider. The individual has almost a full panel of patients but still keeps her panel open for new patient visits. The provider has around 4,200 patient encounters annually with 10% of those being new patient visits and 90% being established patient visits. In addition, the provider bills 10% Level 2, 40% Level 3, 30% Level 4, and 20% Level 5 visits annually.

As you can see above, the revenue impacts the provider at the 99214 and 99215 to a large extent due to the individual seeing primarily established patients. In total, Provider A generated $424,830 in revenue under the current PFS whereas under the proposed the total revenue drops to $408,240. Now, arguably due to the decrease in documentation required and the lack of a need for audits at such regular intervals, the gap should be much narrower. This would only apply in a private practice setting though. In the event the provider is paid based upon a collections model, this gap might not help the provider and could be detrimental from a compensation model standpoint.

With respect to work RVUs, once again the provider is negatively impacted at the Level 4 and Level 5 visits but specifically within the established patient codes. In total, Provider A’s work RVUs under the current PFS go from 5,794 to 5,409. This represents a 7% decrease on the work RVU data and a 4% decrease on the revenue structure. From a compensation modeling standpoint, this change would have a higher impact on work RVU based models than it would on a collections model.

Provider B

Provider B is a new family medicine provider. The individual has been building his panel but ultimately in the first year most visits are new patients. The provider has around 4,200 patient encounters annually with 55% of those being new patient visits and 45% being established patient visits. In addition, the provider bills 5% Level 2, 50% Level 3, 40% Level 4, and 5% Level 5 visits annually.

As noted above, the charts look very similar with respect to their distributional changes. Specifically, overall revenue increases under the proposed rule from $485,079 to $487,620. The work RVUs increase from 6,654 to 6,694. This is an increase of .52% on a revenue basis and .61% on a work RVU basis. In short, the provider with more new patient visits or the provider with more Level 3 visits will benefit. For example, if a provider with the same encounters, percent of new visits, and percent of established visits historically billed 70% at a Level 3 and 20% at a Level 4, revenue under the proposed rule increases by 9.45% and work RVUs by 11.81%.

Commentary

There are a multitude of issues that this type of change could influence. Obviously, the potential issues include revenue structures and provider compensation. However, it also includes potential and significant operational and business strategy changes.

First, this change opens up an opportunity for organizations focusing on low acuity and quick visits for the Medicare population. As noted in the previous example, there is a potential 10% revenue increase if a business is able to capture these less acute issues. It will be interesting to see how the industry reacts from a strategic standpoint in this regard.

Second, from an individual provider perspective although there is a difference between a Level 2 and Level 5 visit, payment will not be based around more complexity. This issue will require organizations to think differently about how they deploy providers to manage chronic illnesses and how private practices see patients.

Finally, one of the less discussed issues relates to production models where providers are primarily employed by health systems. It is no secret that productivity models (work RVUs) form the basis of many compensation models across the country. In addition, many of the behaviors and the operations of those practices are highly influenced by those compensation models. The proposed changes will undoubtedly impact compensation modeling for years to come.

Organizations should ensure that they have an understanding of these changes. As noted on a few of the examples above, you could have a provider who is working the exact same amount but sees a significant decrease in their productivity data. For example, if provider a was paid on a productivity model and received $40 per work RVU, the individual would receive annual income of approximately $232,000. Under the proposed rule, that same individual would receive annual income of approximately $216,000.

Finally, it is worth noting that this type of change will impact nearly all specialties and professions that are paid under the physician fee schedule with a productivity model. The examples noted above focus on primary care relevant data however, there are certainly some specialties that will be highly impacted due to the complexity of patients in which they see. A good example of this might be a cardiology group. Nevertheless, it is important to identify the issues before this proposed rule gets implemented.